Though his 1950 directorial debut Variety Lights wasn’t released in the US until years later, Federico Fellini’s films of that decade were significant contributions to the growing popularity of foreign cinema and arthouses. It was in 1960, however, that he made a movie which probably did more for those things than any single other: The scandalous La Dolce Vita, a three-hour wade into the postwar economic boom’s decadent Rome, an ancient city whose garish embrace of irreligious modernity was regarded with comingled titillation, bemusement, and disapproval. The Vatican condemned it; everybody else queued up, to a degree of commercial success (wherever it wasn’t banned outright) that was staggering for an “art film.”

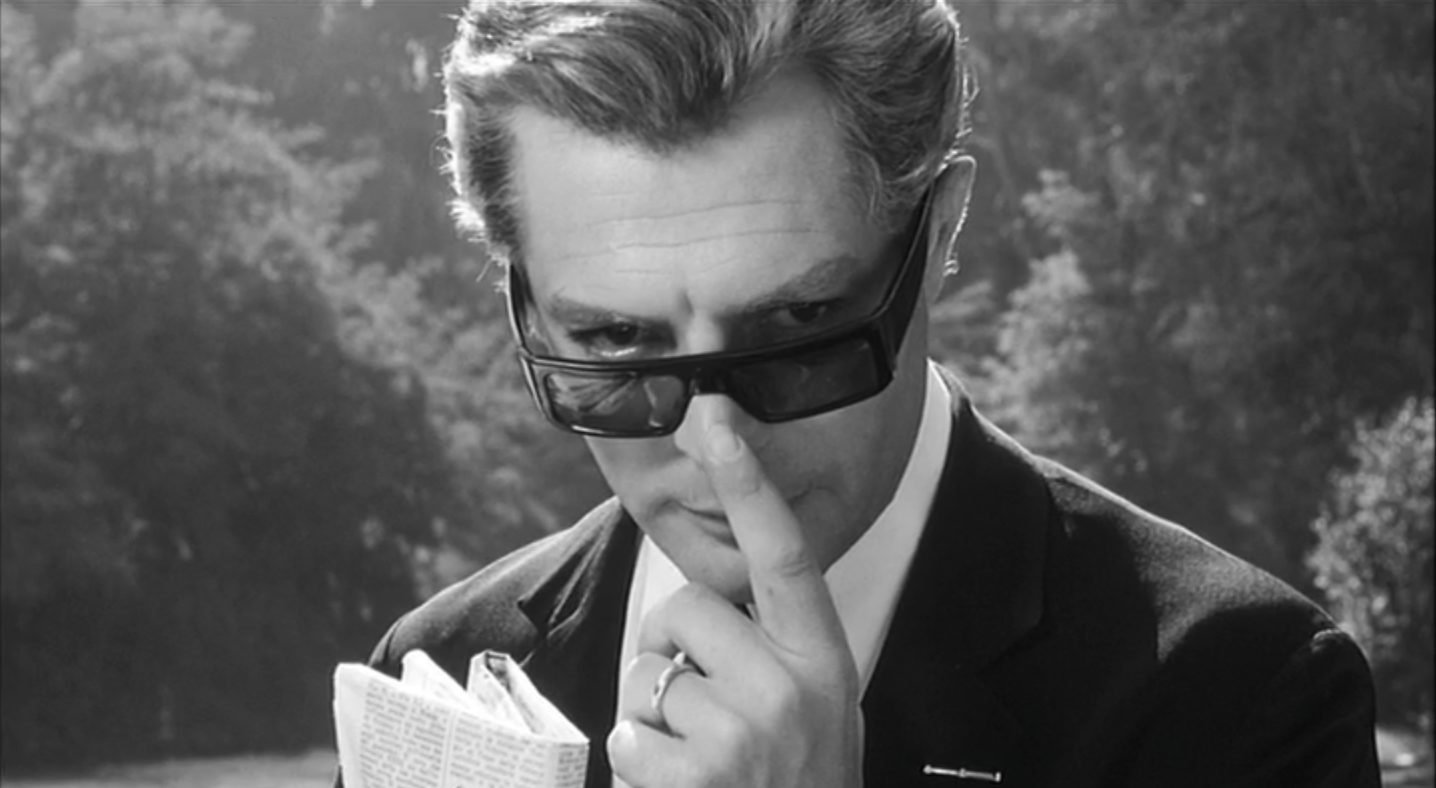

Now-faded shock value aside, La Dolce Vita won prizes and proved an enduring classic because its style was nearly revolutionary: Casting aside his prior neo-realism, Fellini seized on a flamboyance of spectacle, symbolism, aesthetic refinement, and unconventional narrative structure that was endlessly striking as well as provocative. It announced “the film director as superstar” (as a book on that subject would be titled a few years later), not just by making his guiding sensibility so conspicuous, but by having Marcello Mastroianni’s disillusioned journalist an obvious alter ego.

While the nouvelle vague and other movements around the globe would introduce their own directorial “stars” in an extraordinary filmic decade, Fellini remained arguably the biggest Kahuna amongst auteurs through the 1960s. His every release was a major Event even beyond those of Bergman, who was disadvantaged by being more prolific (as well as less fun). Of course criticism also set in, as Fellini’s leap into phantasmagoria prompted not only outside imitators (from the inspired likes of Jodorowsky to myriad cheesy copycats), but also the man himself to sometimes become his own most shamelessly indulgent imitator.

The charges of “Fellini repeating himself” were first leveled at 8 1/2, Vita’s immediate followup, which arrived three years later. Again, Mastroianni was the sardonic yet soulfully droop-lidded witness wandering through a jungle of sin and silliness clamoring for paparazzi attention. (The director is thought to have actually invented that word.) That role was even more nakedly autobiographical this time: He’s a movie director more exhausted than cheered by a recent giant hit, losing himself in fantasies, constantly jarred back to annoying reality by every starlet, colleague, acquaintance, and passer-by who wants a piece of his next “action!”

Even if it struck some at the time as the beginning of a Fellini decline, 8 1/2 was enormously influential in shaping the increasingly “personal” filmmaking of an era in which that artform would be considered the paramount one by many. (To the extent that artists and observers in many other media, from Warhol to Sontag to Mailer, soon felt compelled to make movies of their own.)

It’s also aged better than practically anything you could name whose creation it helped generate. Nearly 40 minutes shorter than Vita, 8 1/2 can seem longer, because its “structure” is so subject to the vagaries of the conscious and dreaming mind. (Fellini also had a famously casual attitude towards adhering to his own scripts.) But it remains dazzling and original, as ambitiously unfettered an exercise in navel- gazing as the movies have ever offered—and the rarest such effort that somehow turns ultimately solipsism into something generous and universal. A new 4K restoration is playing the Roxie’s big house this Sat/28 (4pm), Sun/29 (1:20pm), and Thurs/4 (8:35pm). More info here.

Alongside that nearly 60-year-old monument, the newly released features we caught this week can’t help but seem a little, well, small:

Together

The modesty of scale is deliberate in this Stephen Daldry-directed dramedy by playwright and TV series scribe Dennis Kelly, which indeed premiered on the tube in the UK but is opening in theaters here. It’s another movie about COVID lockdown—we’ll getting those for some time to come, no doubt—in which James McAvoy and Sharon Horgan play an unmarried longterm couple whose relationship had already more or less busted up when the pandemic hits. Sucking it up, they move back in together for the sake of their only child, 10-year-old Artie (Samuel Logan). Though as he’s withdrawn to the point of being virtually mute, one guesses being around Mom and Dad’s incessant squabbling isn’t doing him all that much good.

Strangely, the script doesn’t explore that, keeping Artie well in the background even as these characters never leave the house. Instead, we get the adult stars tearing into one another with sour bitch quips when not delivering monologues to the camera, plus the occasional mutual soul-searching. Some of Kelly’s writing is very sharp, and there’s no question these actors are very capable. But should they have to make so much of so little?

At first it seems refreshing that Together dramatizes a COVID quarantine experience that’s surely been common in real life, but left unexplored onscreen: How lockdown boredom and claustrophobia might exacerbate the worst in relationships. Caving to sentimentality, however, the film eventually betrays that truth for the sake of a happy ending we can scarcely swallow, because these two ill-matched people don’t belong together. The film has its admirers. But apart from the acting fireworks it often seems to exist solely to ignite, you may well find it exactly as punishing as 90 minutes spent in the company of any other couple who can’t stand each other. It opens Fri/27 at Bay Area theaters including the Embarcadero, Kabuki and Shattuck.

Ma Belle, My Beauty

By contrast, this breezy drama by writer-director Marion Hill is all about openness—to the countryside of picturesque Southern France, to polyamory and bisexuality. Of course, as in nearly all such tales, too much freedom of choice brings conflict as well as titillation. Singer Bertie (Idella Johnson) has moved to a lovely wine country villa in that locale with musician spouse Fred (Lucien Guignard). Still, she hasn’t performed in months, apparently experiencing some kind of artistic block.

Thus Fred “surprises” her with a visit from Lane (Hannah Pepper), whom they knew back in New Orleans—in fact, the two women were lovers then. Free-thinking (if also calculating) hubby seems to think the reunion will get his wife’s, um, creative juices flowing again. Bertie finds this new wrinkle unsettling as well as enticing, however, and is alarmed by her own jealousy when a politely-refused Lane cheerfully turns toward a sexy visiting Israeli painter (Sivan Noam Shimon as Noa) for companionship.

This is the kind of gauzy, near-plotless erotica that aims to provide a brief vacation in itself—the escapism of watching pretty people in enviable settings toy with one another’s desires, whether actually in bed or in time-killing scenic montages. There’s not much of a script here, and at times one wonders if Ma Belle came together primarily to take advantage of an extended French holiday. However, its aromatic frisson of wine, sex and culture may be just what the doctor ordered for some viewers amidst our cold SF summer and seemingly endless pandemic precautions. I can’t say it did much for me. Still, the vicarious pleasures it offers are the kind you can hardly begrudge anyone else enjoying. It opens Fri/27 at the Embarcadero and Shattuck Cinemas.

When I’m a Moth

Pleasant insubstantiality is one thing, exasperating pointlessness quite another. There’s a world-class example of the latter in this stupefying feature, which was shot in 2016, premiered at SFFilm in 2019, and is now finally getting released—during which timespan co-directors Zachary Cotler and Magdalena Zyzak completed two other, better films. Beginning from the first artily icky close-up of fish guts, you will understand why Moth has spent so long on the shelf. Why it got made in the first place, however, remains a mystery.

The germ of truth here is that in 1969, newly college-graduated Hilary Rodham (pre-Clinton) briefly went to work in the fisheries of Alaska, soon giving up and going home after getting fired for being too slow. The filmmakers dispose of that factoid in the first few minutes here, then occupy nearly 90 more with a rudderless fiction in which their pushy, self-absorbed, endlessly nattering Young Hilary (Addison Timlin) meets a couple unemployed Japanese fishermen (Toshiji Takeshima, TJ Kayama). she decides to hang out with them, somewhat to their bewilderment, especially as they don’t really share any common language.

This future Secretary of State absurdly clomps around the wilderness in a “power red” ensemble, seeming to anticipate her future by spouting political-philosophical doggerel that, like the commingled pomposity and self-loathing with which she carries herself, represent a sort of character assassination. If that were the point here, it might be lamentable, but at least would be cogent.

Unfortunately, Moth only clouds its raison d’etre further by adopting an undeniably handsome yet wildly irrelevant (not to mention pretentious) metaphysical style akin to films by Russia’s Aleksandr Sokurov, with lens distortions and a soundtrack full of avant-garde composers. Credit is due cinematographer Lyn Monchief, and actor Timlin, who tries her best under impossible circumstances. But their contributions aside, this is the kind of conceptual boondoggle you have to see to believe. Be warned, though: It’s a fingernails-on-chalkboard kind of bad movie, not the fun kind. You will laugh, you will cry—but both from sheer pain. When I’m a Moth is available on major digital platforms as of Fri/27.

"dazzling" - Google News

August 28, 2021 at 12:31AM

https://ift.tt/3DlF26C

Screen Grabs: The dazzling longevity of Fellini's '8 1/2' | 48 hills - 48 Hills

"dazzling" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2SitLND

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Screen Grabs: The dazzling longevity of Fellini's '8 1/2' | 48 hills - 48 Hills"

Post a Comment